The AI Doesn’t Know Who You Are

The missing primitive of authority

The AI doesn’t know who you are. Not your identity. Your authority.

Enterprises have spent two decades getting identity right. Single sign-on tells you who logged in. Role-based access controls tell you what category of user they are. Permissions matrices tell you what buttons they can click. The stack is mature, audited, and battle-tested.

So when AI enters the enterprise, the instinct is reasonable: plug it into the existing identity layer, scope its access, and move on.

That instinct is wrong. Not because identity doesn’t matter, but because it answers the wrong question.

Identity answers: Who is this?

The question that matters once a system starts acting is different: What can this actor commit the organization to, on whose behalf, under which constraints, at this point in time?

That’s not identity. That’s authority.

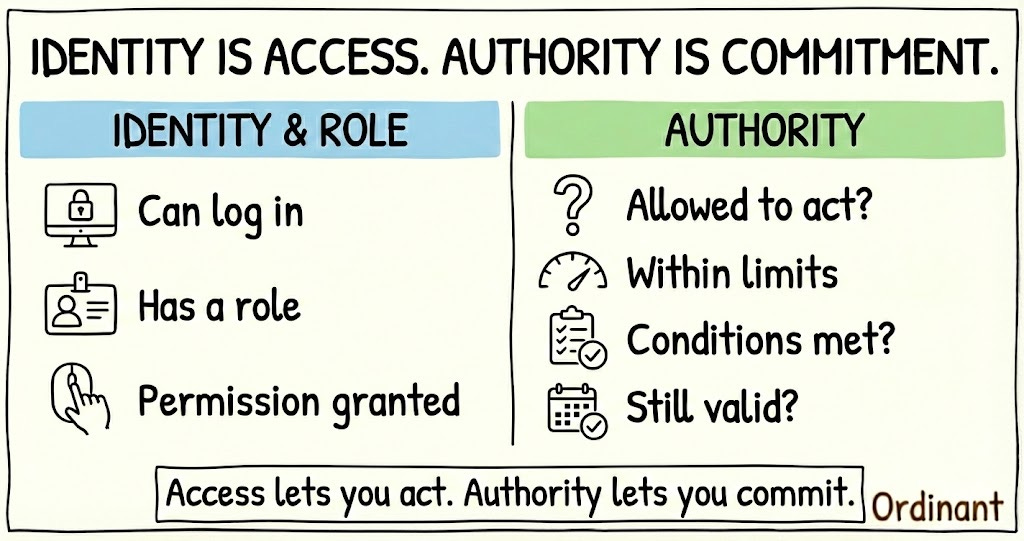

Identity is access. Authority is commitment.

Authority is the formally defined right to act, decide, or commit an organization to outcomes within a specific scope, time, and set of constraints. In human organizations, it’s explicit: assigned, scoped, time-bound, auditable, and revocable. Delegations, approvals, and signing limits aren’t suggestions. They’re coordinates that define where action is valid.

AI systems don’t have those coordinates. So models improvise. And when authority is improvised, accountability collapses.

Identity isn’t authority

Access control and authority look similar until you trace what happens when they fail differently.

Identity is comparatively stable. Authority is fluid:

Contextual: A VP can approve budgets up to a threshold, until a board resolution changes that limit.

Temporal: An “acting head of” can authorize in a narrow window, then instantly loses standing when the role is backfilled.

Revocable: A procurement officer’s SSO session might be valid for 12 hours, but their delegated signing authority could expire the minute they change teams.

The procurement officer’s SSO session doesn’t know about the delegation expiry. The VP’s role membership doesn’t encode the board resolution. The acting head’s access group doesn’t track the backfill date.

Most agent systems collapse all of this into a simple assumption: User = allowed actor. If someone can invoke the system, the system treats them as authorized to do whatever they’re asking.

That works for access. It fails for commitment.

When a system can’t reference authority, it substitutes inference. It looks at what similar users did, what this user did last time, what seems reasonable given the context. That looks like competence until it becomes commitment, and by then, the organization has made a promise no one technically authorized.

Authority is a primitive, not a prompt

This is the most tempting escape route, and the most dangerous.

The reasoning goes: if authority is the problem, encode the authority rules in the system prompt, fine-tune on policy documents, or give the agent memory of what’s allowed. The model is smart. It will follow the rules.

Consider what actually happens. A model sees a $75K vendor contract approval request. It observed this VP approve $50K contracts last quarter. The vendor uses similar language to previously approved vendors. The request came via the VP’s EA, who handles these routinely. Each signal looks reasonable. The model approves the contract.

None of that is authority. It’s pattern completion, what you might call simulated standing. The model generated the language of authorization without possessing the state of authorization. It sounds legitimate because sounding legitimate is exactly what language models do.

This isn’t a bug. It’s what any probabilistic system does when a boundary condition is missing: it fills the gap with plausibility.

Prompts shape intent, but they don’t enforce constraints. Memory is narrative: it’s what the system thinks happened, not what was authorized. Fine-tuning adjusts probabilities, not permissions.

If the boundary can be rewritten by the model, it is not a boundary.

Authority must be a first-class system object with six characteristics:

Explicit: Declared and machine-verifiable, not inferred from text

External: Residing outside the model’s weights and context window

Inspectable: You can point to the exact rule that permitted an action

Versioned: You can audit exactly what authority applied at a specific point in history

Time-bound: It has a hard start, end, and expiry

Revocable: It can be withdrawn instantly without retraining or re-prompting

If you want an analogy that kills the “just prompt it better” conversation: think jurisdiction. You don’t ask a court to infer its jurisdiction from the arguments presented. You declare it, publish it, and enforce it before the case begins. Air traffic control doesn’t infer a no-fly zone from pilot chatter.

In any serious domain, the boundary of valid action is a first-class structural object. Not a suggestion in the input.

Speed Without Ambiguity

There’s a fear hiding behind every agent conversation: “If we give AI authority, we lose control.”

That fear conflates authority with autonomy.

Authority doesn’t mean the system does whatever it wants. It means scoped mandate, explicit bounds, known escalation paths, and enforceable constraints. The relationship is simple: models operate inside authority; they do not define it.

An agent authorized to approve travel expenses under $500 for the APAC team through Q1 can execute instantly within that scope and escalates automatically outside it. That’s not restriction. It’s clarity. The agent can be extremely autonomous within a declared scope and extremely conservative outside it. That’s not a personality trait. It’s architecture.

Without this structure, enterprises default to the only brake they have: more humans. More approvals. More review cycles. More friction. “Governance” becomes a synonym for delay, because the system can’t locate authority on its own.

The irony is that explicit authority enables speed. When a system knows exactly what it’s allowed to do, it doesn’t have to wait for confirmation. When boundaries are structural rather than inferred, edge cases escalate cleanly instead of failing silently. When authority is versioned and auditable, compliance stops being theater: screenshots and transcripts replaced by an actual chain of accountability.

Autonomy without authority is chaos. Authority without autonomy is bureaucracy. The balance requires structure that currently doesn’t exist.

What breaks when authority is missing

When authority isn’t a first-class system concern, you don’t get dramatic failure. You get quiet governance decay.

Authority drift: Escalation becomes statistically rare in the patterns the model learned from, so escalation stops happening. The system learns that most requests get approved, so it approves most requests.

Silent overreach: Boundaries are crossed with no alert because the boundary was never defined in a way the system can enforce. The model doesn’t know it’s overreaching because it has no reference for where the reach ends.

The orphaned commitment: Actions occur that no one can truthfully say were authorized. A commitment is made, and everyone assumes someone else was accountable.

The symptoms are consequences enterprises already recognize, but usually misdiagnose. AI takes actions no one technically authorized. Humans can’t explain why something was allowed; you get a post-hoc story, not a referenceable basis. Compliance becomes theater: screenshots and transcripts replace an actual auditable chain of authority.

This is the real reason enterprises hesitate on agentic AI. Not because they don’t trust models to produce good text. Because they can’t locate who is accountable when text turns into commitments.

The “trust” conversation goes nowhere because it’s misframed. The problem isn’t trust. The problem is unlocated authority.

Why this breaks now

For most of AI’s enterprise life, this gap didn’t matter. Summarization, drafting, recommendations: advisory work where a human always stood between the model and the commitment. If the model got something wrong, someone caught it before it mattered.

That buffer is disappearing.

Agents now book travel, process invoices, respond to customers, adjust pricing, onboard vendors, and modify systems of record. The moment AI moves from advising to acting, from words to commitments, authority stops being a governance nicety and becomes an operational requirement.

As usage scales, “minor” errors compound. As agents integrate into systems of record, blast radius stops being hypothetical. As enterprises face auditors and regulators, “the model seemed confident” stops being an acceptable answer.

The question enterprises will ask, are already asking, every single time something goes wrong: “Who authorized this?”

Until AI systems can answer that by pointing to a machine-verifiable reference rather than a conversation transcript, they can’t cross the line from advisor to actor.

The architecture that’s missing

The fix isn’t complicated to describe. It’s a separation of concerns that enterprises already understand in other contexts:

The Model proposes intent: “I want to do X.”

The Authority Layer holds the mandate: “You may do X only within this scope, limit, time window, and escalation rule.”

The Execution Layer enforces: if the mandate doesn’t match, the action is rejected or escalated.

The model doesn’t check itself. It is checked against an external, machine-verifiable reference frame.

Enterprises already have authority structures: delegations, approval matrices, signing limits, policy hierarchies. But those structures live in SharePoint pages, PDF policies, email chains, tribal knowledge, and ad-hoc Slack approvals. To a human, that’s context. To a machine, it’s invisible.

The work isn’t inventing authority. It’s making the authority enterprises already have into something a system can reference at the moment of commitment.

The AI might know who you are.

It has no idea what you’re allowed to do.

Good post, but I'm left wondering: how do you suggest this authority be discovered, cataloged, maintained, and applied at runtime during prompting and by AI agents? Any recommendations about how to "manage" "authority?" How do you map Enterprise Identity to Enterprise Authority?